In general, acoustics is the science of sounds. Sounds have always played a special role in the life of any person, as they allow people to navigate space, communicate, watch movies and listen to their favorite music.

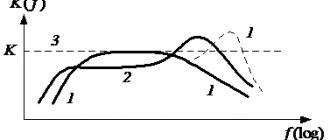

Figure 1. Varieties of acoustics. Author24 - online exchange of student work

The use of acoustics is in demand in absolutely all areas, from construction to medicine. This scientific section studies the vibrations of sound waves, the principles of their formation and distribution.

Are you an expert in this subject area? We invite you to become the author of the Directory Working Conditions

Definition 1

Acoustics is a broad field of physics that studies elastic vibrations and waves from the lowest frequencies to the highest.

A person begins to hear sound through constant vibrations produced at a certain frequency. One of the main definitions of acoustics is a sound wave, which is a vibration whose pressure directly depends on the source. For example, a car horn signal carries a higher vibration than a human whisper. Sound intensity is always measured in decibels.

Modern acoustics covers a fairly wide range of issues; it includes a number of important subsections:

- physical acoustics - studies the features of the propagation of elastic waves in various spaces;

- physiological acoustics - describes the structure and operation of sound-producing and sound-perceiving organs in humans and animals.

In a narrower sense of the word, acoustics should be understood as the study of sound, that is, elastic vibrations in gases, solids and liquids perceived by the human ear. A sound wave can be reflected from surfaces, scattered in them, or absorbed. The reflection parameter of the sound force is determined by what acoustic characteristics it has and what the sound wave has passed through.

Finished works on a similar topic

Course work The concept of acoustics in physics 410 ₽ Abstract The concept of acoustics in physics 250 ₽ Test work The concept of acoustics in physics 250 ₽

Receive completed work or specialist advice on your educational project Find out the cost

The nature of sound and its physical characteristics

Figure 2. Physical characteristics of sound. Author24 - online exchange of student work

Sound waves and vibrations are a special case of mechanical changes. However, due to the importance of acoustic definitions for the correct assessment of auditory sensations, as well as because of the medical application, it would be advisable to examine some issues in more detail.

Today it is customary to distinguish the following sounds:

- tones, or musical sounds;

- noises;

- sonic booms.

Tone is a periodic process of sound. If this process is completely harmonic, then the tone is called pure or full, and the corresponding sound plane wave is described by the corresponding equation. The key physical characteristic of this type of sound is frequency. Anharmonic vibration corresponds to a complex tone. A simple tone is formed, for example, by a tuning fork, but a complex tone can be heard thanks to musical instruments.

The lowest frequency of decomposition of a complex tone into simpler structural units corresponds to the fundamental tone; the remaining overtones in this case have frequencies equal to $2νο$, $3νο$ and so on.

Definition 2

A set of vibrations with an indication of their specific intensity (amplitude A) is called an acoustic spectrum in physics.

The spectrum of a complex tone is always lined. Thus, the acoustic spectrum is one of the most important physical characteristics of musical sounds, since it can be distinguished by a complex, non-repeating time dependence.

Researchers include noise from car vibrations, applause, rustling, burner flames, creaking, consonant sounds of speech, and so on. This sound type can be considered as a combination of chaotically changing complex tones

Definition 3

A sonic boom is a short-term, uniform sound impact in the form of an explosion or pop.

A sonic boom should not be confused with a shock wave, the frequency of which is much higher.

Main directions of modern acoustics

Numerous scientific works on the study of the nature of noise and the issues of noise reduction and sound insulation were published some time later. The first work in this area concerned mainly the noise produced by aircraft and ground transport. But over time, the boundaries of these studies have expanded significantly. At the moment, most industrialized countries have their own research institutes that are engaged in developing solutions to these problems.

Today, the following sections of acoustics are best known: general, geometric, architectural, construction, psychological, musical, biological, electrical, aviation, transport, medical, ultrasound, quantum, speech, digital. The following chapters will examine some of these areas of sound science.

Wave nature of sound

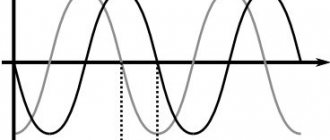

Figure 3. Wave nature of sound. Author24 - online exchange of student work

To better define the system for the appearance of a sound wave, it is necessary to imagine a classic speaker located in a pipe, which is filled to the brim with air. If this device suddenly moves forward, the air in the immediate vicinity is compressed for a moment. After this, the air gap will expand, pushing the compressed area of air along the pipe.

It is this wave motion that will subsequently become sound when it reaches the auditory organ and “excites” the eardrum. When a sound wave occurs in the gas, excess internal pressure and unnecessary density are formed and particles are transformed at a constant speed. When studying sound and its features, it is important to remember the fact that material matter does not move in proportion to the sound wave, but only a temporary disturbance of the acting air masses appears.

Note 1

If the particles vibrate along the direction of wave propagation, then the wave sound is called longitudinal, but if they vibrate directly perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation, then the wave is called transverse.

Typically, sound tones in liquids and gases are longitudinal, but in solid physical bodies the formation of waves of both types is possible. Transverse waves in material bodies arise through resistance to changing the original shape. The key difference between these two types of waves is that the transverse wave is equipped with the property of polarization, while the longitudinal wave is not.

Anecdote from life

Nevertheless, even at present, not all manufacturers of industrial equipment pay at least some attention to this issue. The management of not all plants and factories is concerned about maintaining healthy hearing among their subordinates.

Sometimes you hear stories like this. The chief engineer of one of the large industrial enterprises ordered the installation of microphones in the noisiest workshops, connected to loudspeakers located outside the buildings. In his opinion, in this way the microphones will suck some of the noise out. Of course, as comical as this story is, it makes you think about the reasons for such illiteracy in matters relating to noise reduction and sound insulation. And there is only one reason for this - in educational institutions of higher, secondary vocational and secondary specialized levels of education, only in recent decades have they begun to introduce special courses in acoustics.

further reading

- Benade, Arthur H (1976). Fundamentals of Musical Acoustics

. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 2270137. - S.V. Biryukov, Yu.V. Gulyaev, V. Krylov, V. Plesssky (1995). Surface acoustic waves in inhomogeneous media.

,Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-58460-5. - M. Crocker (ed.), 1994. Encyclopedia of Acoustics

(Interscience). - Falkovich, G. (2011). Fluid Mechanics, a short course for physicists

. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00575-4. - Frank J. Fahey; Paolo Gardonio (2007). Sound and structural vibration: Radiation, transmission and response

(Second ed.). Academic press. ISBN 978-0-08-047110-5. - M. C. Junger and D. Feit (1986). Sound, Structures and Their Interactions

, 2nd edition, MIT Press. - L. E. Kinsler, A. R. Frey, A. B. Coppens, and J. W. Sanders, 1999. Fundamentals of Acoustics,

Fourth Edition (Wiley). - Mason W.P., Thurston R.N. Physical Acoustics

(1981) - Philip M. Morse and C. Uno Ingard, 1986. Theoretical Acoustics

(Princeton University Press). ISBN 0-691-08425-4 - Allan D. Pierce, 1989. Acoustics: An Introduction to Its Physical Principles and Applications

(Acoustical Society of America). ISBN 0-88318-612-8 - Reichel, D. R., 2006. The Science and Application of Acoustics,

Second Edition (Springer). ISBN 0-387-30089-9 - Rayleigh, J. W. S. (1894). Theory of Sound

. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-8446-3028-1. - E. Skudzik, 1971. Fundamentals of Acoustics: Fundamentals of Mathematics and Fundamentals of Acoustics

(Springer). - Stephens, R. W. B.; Bate, A. E. (1966). Acoustics and vibration physics

(2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold. - Wilson, Charles E. (2006). Noise Control

(Revised ed.). Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57524-237-8. OCLC 59223706.

see also

- Acoustics outline

- Acoustic attenuation

- Acoustic emissions

- Acoustic engineering

- Acoustic impedance

- Acoustic levitation

- Acoustic location

- Acoustic phonetics

- Acoustic broadcast

- Acoustic tags

- Acoustic thermometry

- Acoustic wave

- Audiology

- Auditory illusion

- Diffraction

- Doppler effect

- Acoustics for fishing

- Helioseismology

- Lamb Wave

- Linear elasticity

- Red Book of Acoustics

(in the United Kingdom) - Longitudinal wave

- Music therapy

- Noise pollution

- Phonon

- Picosecond ultrasound

- Rayleigh wave

- Shock wave

- Seismology

- Sonification

- Sonochemistry

- Soundproofing

- Soundscape

- shock wave

- Sonoluminescence

- Surface acoustic wave

- Thermoacoustics

- Transverse wave

- Wave equation

Professional societies

- Acoustical Society of America (AS)

- Australian Acoustical Society (AAS)

- European Acoustical Association (EAA)

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

- Institute of Acoustics (IoA UK)

- Audio Engineering Society (AES)

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Noise and Acoustics Division (ASME-NCAD)

- International Commission on Acoustics (ICA)

- American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Aeroacoustics (AIAA)

- International Computer Music Association (ICMA)

Acoustic scale

Hypersound is elastic waves with frequencies from 101000 to 1012-1018 Hz. By its physical nature, hypersound is no different from sound and ultrasonic waves. Hypersound is often represented as a stream of quasiparticles - phonons

.

In nature, it is generated by vibrations of atoms at the sites of a crystal lattice, and its wavelength is equal to the average path of a molecule before it collides with another.

Ultrasound - with a frequency greater than 20 kHz.

Normal sound (audible to the human ear) is from 20 Hz to 20 kHz.

Infrasound - with a frequency of less than 20 Hz.

Recommendations

- "What is Acoustics?", Acoustics Research Group

, Brigham Young University - Quotation error. See inline comment for how to fix.[ verification required

] - Quotation error. See inline comment for how to fix.[ verification required

] - Quotation error. See inline comment for how to fix.[ verification required

] - Quotation error. See inline comment for how to fix.[ verification required

] - Quotation error. See inline comment for how to fix.[ verification required

] - K. Boyer and W. Merzbach. History of mathematics.

Wiley 1991, p. 55. - "How Sound Travels" (PDF). Princeton University Press. Retrieved February 9, 2016. (quoted from Aristotle's Treatise on Sound and Hearing

) - Whewell, William, 1794–1866 History of inductive sciences: from ancient times to the present day.

Volume 2 . Cambridge. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-511-73434-2. OCLC 889953932.CS1 maint: multiple names: list of authors (link) - Greek Musical Works

. Barker, Andrew (1st ed. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2004. p. 98. ISBN 0-521-38911-9. OCLC 63122899.CS1 maint: others (communications) - ACOUSTICS, Bruce Lindsay, Dowden - Hutchingon Books, Chapter 3

- Vitruvius Pollio, Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture

(1914) Tr. Morris Hickey Morgan Book V, sections 6–8 - Vitruvius article @Wikiquote

- Ernst Mach, Introduction to the Science of Mechanics: a critical and historical account of its development

(1893, 1960) Tr. Thomas J. McCormack - Sparavigna, Amelia Carolina (December 2013). "The Science of Al-Biruni" (PDF). International Journal of Sciences

.

2

(12): 52–60. arXiv:1312.7288. Bibcode:2013arXiv1312.7288S. Doi:10.18483/ijSci.364. S2CID 119230163. - "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni." School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. November 1999. Archived from the original on 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- Pearce, Allan D. (1989). Acoustics: An Introduction to Its Physical Principles and Applications

(1989 ed.). Woodbury, New York: Acoustical Society of America. ISBN 0-88318-612-8. OCLC 21197318. - Schwartz, S. (1991). Chambers' Concise Dictionary

. - Acoustical Society of America. "PACS 2010 Regular Edition - Acoustics Supplement." Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ a b

Clemens, Martin J. (January 31, 2016).

"Archaeoacoustics: Listening to the Sounds of History." The Daily Grail

. Received 2019-04-13. - ^ a b

Jacobs, Emma (13 April 2017).

"Using archaeoacoustics, researchers search for clues to the prehistoric past." Atlas Obscura

. Received 2019-04-13. - da Silva, Andrei Ricardo (2009). Aeroacoustics of Wind Instruments: Research and Numerical Methods

. VDM Verlag. ISBN 978-3639210644. - Slaney, Malcolm; Patrick A. Naylor (2011). "Trends in Audio and Acoustic Signal Processing". ICASSP

. - Morpheus, Christopher (2001). Dictionary of Acoustics

. Academic press. paragraph 32. - Templeton, Duncan (1993). Acoustics in the Built Environment: Tips for Designers

. Architectural press. ISBN 978-0750605380. - "Bioacoustics - International Journal of Animal Sounds and Recordings." Taylor and Francis. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- Acoustical Society of America. “Acoustics and You (Careers in Acoustics?).” Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- Krylov, V.V. (Ed.) (2001). Noise and vibration from high speed trains

. Thomas Telford. ISBN 9780727729637 .CS1 maint: additional text: list of authors (link) - World Health Organization (2011). Burden of disease from environmental noise

(PDF). WHO. ISBN 978-92-890-0229-5. - Kang, Jian (2006). Urban Sound Environment

. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0415358576. - Technical Committee on Musical Acoustics (TCMU) of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA). "Home page of TKMU ASA". Archived from the original on 2001-06-13. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- Iakovides, Stefanos A.; Iliad, Vasiliki TH; Bizeli, Vasiliki TD; Kaprinis, Stergios G.; Fountoulakis, Konstantinos N.; Caprinis, George S. (March 29, 2004). "Psychophysiology and psychoacoustics of music: perception of complex sound in normal subjects and psychiatric patients." Annals of Hospital Psychiatry

.

3

(1): 6. doi:10.1186/1475-2832-3-6. ISSN 1475-2832. PMC 400748. PMID 15050030. - "Psychoacoustics: the power of sound." Memtech Acoustical

. 2016-02-11. Received 2019-04-14. - ^ a b

Green, David M. (1960).

"Psychoacoustics and Detection Theory". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

.

32

(10):1189–1203. Bibcode:1960ASAJ...32.1189G. Doi:10.1121/1.1907882. ISSN 0001-4966. - "Technical Committee on Speech Communication." Acoustical Society of America.

- Ensminger, Dale (2012). Ultrasound: Fundamentals, Technologies and Applications

. CRC Press. pp. 1–2. - Lohse, D., Schmitz, B., and Versluis, M. (2001). "Snapping shrimp make flashing bubbles." Nature

.

413

(6855):477–478. Bibcode:2001Natura.413..477L. Doi:10.1038/35097152. PMID 11586346. S2CID 4429684. - ASA Technical Committee on Underwater Acoustics. "Underwater acoustics". Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- "Technical Committee on Structural Acoustics and Vibration." Archived from the original on August 10, 2022.